Berthon Remembers for VE Day

May 7th, 2020

Berthon has a long and proud history as part of the beautiful New Forest, and as frontrunners in the British marine construction industry throughout World War two.

As we approach VE day, and particularly at a time where the national zeitgeist is one of personal reflection, we bring you a (very!) brief insight into Berthon’s history during World War ll, as well as a few stories of our own families.

As the cacophony of 1939 and the inevitability of another war raged on, Britain ramped up domestic production to deal with an imminent international conflict. Notable figures within the boat-building industry, including Hubert Scott-Paine and Peter du Cane, tried early-on to persuade the Navy of the need for technologically advanced high-speed motor launches, correctly anticipating that the dynamic of the Second World War would be one of industrial advancement: a war of capability and innovation as opposed to simple sheer volumes of resource and manpower that the gruelling First World War had demanded. Frustratingly slow on the uptake, the Royal Navy eventually realised they would be fighting a new form of marine warfare and began to commission research, development and production of more types of high-speed crafts, to meet a very different threat. More can be seen on this in our historic boats article, here.

Different classes of motor launch were developed at unprecedented speeds, and manufacture was equally rapidly accelerated. Shipyards and boat-builders along the South coast were drafted to produce boats for the armed forces. Shortly, the majority of construction had the sole purpose of assisting with the war effort and the construction and repair of leisure yachts was swiftly abandoned in favour of determinedly war-assisting offerings.

Interestingly, in the earlier years of the war, recreational sailing was not entirely prohibited. Seen as a gentle respite from the duties of war, several sections of the Solent were deemed leisure sailing areas, provided boats were clearly labelled and adhered to strict curfews. Soldiers stationed in Lymington were able to enjoy the hospitality of the small yacht clubs and engage in carefully regulated sailing for entertainment.

As the war progressed however, these restrictions became tighter and tighter as the threat edged closer to British soil. Eventually, sailing was prohibited with leisure vessels ordered to remove specific engine components to render them useless; the British government keen to leave absolutely no usable engines for potential successful German invaders. All yachts were painted grey and hundreds lined the rivers of the south coast, left on their moorings to await the return of peace – and their owners. Significant fines were levied on those breaking the rules by taking vessels out for recreational purposes into the ever-more-dangerous Solent waters, or not immobilising their engines. Missiles, torpedoes and submarines were becoming well-known dangers – most recently in the news was the suspected German SC250 bomb found in Portsmouth Harbour whilst dredging was underway in 2017 and others found poking their noses out of the shingle banks along Milford to Hurst castle, after the odd severe storm!

Meanwhile between 1939 and 1945, Berthon was commissioned to build 215 boats, including a variety of Minesweepers, Harbour Defence Motor Launches (HDML, for which Berthon became specialists) and Assault Landing Craft – at record pace. Despite the international crisis, business at Berthon boomed, with the yard producing boat after boat for the Admiralty. Many of our current staff’s grandparents were employed by Berthon during this time, with generations of boat-builders to be found in the local area.

Meanwhile between 1939 and 1945, Berthon was commissioned to build 215 boats, including a variety of Minesweepers, Harbour Defence Motor Launches (HDML, for which Berthon became specialists) and Assault Landing Craft – at record pace. Despite the international crisis, business at Berthon boomed, with the yard producing boat after boat for the Admiralty. Many of our current staff’s grandparents were employed by Berthon during this time, with generations of boat-builders to be found in the local area.

As the war continued and the British maritime capability became formidable, following significant Naval funding and much commitment to development, Berthon continued to produce boats on what resembled a production line for military vessels. The Solent has been described as a ‘Picadilly Circus’ of craft at sea toward the end of the war, with a decent portion of marine traffic originating from Lymington.

The war began to draw to a close, with the longer term effects on the South coast coming to light. Petrol was a rare commodity, but with restrictions on boaters being lifted, there was – as one accounts notes – thankfully no restriction on the wind! With the results of rationing and national shortages proving extremely hard, small boat sailing was once again a welcome reprieve from the reality of post-war Britain.

As is mirrored in the Berthon of today, having weathered the storm well, the business was able to retain workers and support local families. Despite the extreme conditions, Berthon continued – and continues – to operate through hard times. Incidentally, Berthon has recently welcomed many WWII vessels back to the yard for important repair, refit and maintenance work. The full restoration process, including engine replacements, of the Motor Gun Boat ‘81’ can be enjoyed here. The photo below is of HSL102 in the West Solent Shed, tucked away at lockdown and now soon to be worked on to repair a shaft bracket problem.

A more detailed history of Berthon’s exact wartime production, including details about the vessels themselves, the trials that Berthon faced and the company decisions, culminating in J.O. May becoming chairman in 1942 can be found in the second instalment of Philip Bristow’s research for a book ‘The Berthon Story, The History of the Berthon Boat Company’, yet to be printed.

Berthon personally remembers

As aforementioned, many of Berthon’s staff were involved in the Second World War; both at Berthon and overseas. We spoke to a few of our staff to find out their personal histories and memories.

Sophie Kemp of Berthon International spoke to her Grandfather for us: “I remember the first ‘trial’ air raid siren in 1939 and subsequently teachers coming to our house to take classes in the front room, while shelters were built at school. Dad built a posher-than-most Anderson air-raid shelter in the garden. Our neighbours were in ours playing cards when their shelter 20 feet away was destroyed by a misfired anti-aircraft shell: that was close! We accepted extensive bomb damage as ‘normal’ and would forage bombsites claiming to have found body parts (‘I’ve got a finger!’) Thankfully we never found anything. Grandma and I were once blown across the room by a nearby V2 as the windows went in. She never, ever, showed or expressed fear. The effects of the world war lasted for years.”

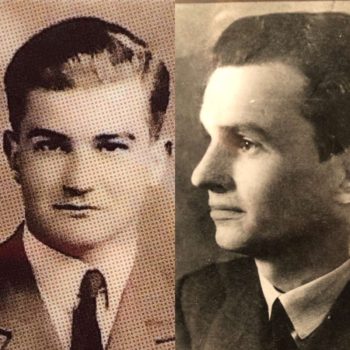

Seen to the right here was Squadron Leader Richard Chudleigh, with his best friend and co-pilot Jack Ayliffe to the left. A World War two flying ace, Chudleigh flew together with Ayliffe throughout the war until they crashed in Dordogne around a month before peace was declared. Sadly, Ayliffe didn’t survive the crash and a fitting memorial to him stands to this day in France, with the propeller of their plane ‘Mosquito’ marking his resting place. Richard Chudleigh was the Father of Isabel Moss, who works at Berthon International.

Seen to the right here was Squadron Leader Richard Chudleigh, with his best friend and co-pilot Jack Ayliffe to the left. A World War two flying ace, Chudleigh flew together with Ayliffe throughout the war until they crashed in Dordogne around a month before peace was declared. Sadly, Ayliffe didn’t survive the crash and a fitting memorial to him stands to this day in France, with the propeller of their plane ‘Mosquito’ marking his resting place. Richard Chudleigh was the Father of Isabel Moss, who works at Berthon International.

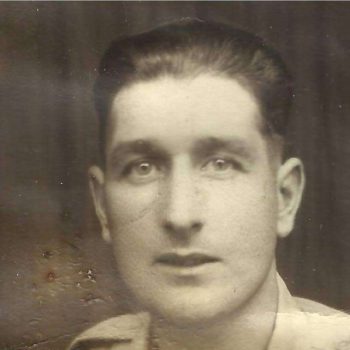

This is Melvyn Tom Cole. Father of our very own Melyvn Cole of the Dockmaster team (where he started in 1978!), Melvyn Cole senior was stationed in Sri Lanka from 1939 to 1947 as an Army electrician, assisting the build of a radar station. He returned to the UK and was subsequently employed at Berthon, where he was fondly known as Tom.

This is Melvyn Tom Cole. Father of our very own Melyvn Cole of the Dockmaster team (where he started in 1978!), Melvyn Cole senior was stationed in Sri Lanka from 1939 to 1947 as an Army electrician, assisting the build of a radar station. He returned to the UK and was subsequently employed at Berthon, where he was fondly known as Tom.

Seen here is the grandfather of our Marketing Manager Helen Davison. Son of a German father, Helen’s Grandad was naturalised as English aged 21. When the world war began, Hitler’s forces called on him to sign up for them. He refused, due to being an English citizen. They sent him a notice that he would be executed if were ever to return to Germany. He subsequently joined the Royal Engineers and was assigned a job as a dispatch rider serving in both Italy and Africa. He would deliver messages back and forth up the lines where the army were engaged in providing construction logistics.

Berthon’s Digital content executive Harry Shutler’s grandfather – John Malcolm Wright – was running for an armoured truck whilst under fire, and tried to shelter underneath the vehicle after the doors were closed. Not as armoured as they had been led to believe, John was shot in the throat, thankfully not fatally, and saw VE Day out from a hospital in Scotland.

Berthon’s Digital content executive Harry Shutler’s grandfather – John Malcolm Wright – was running for an armoured truck whilst under fire, and tried to shelter underneath the vehicle after the doors were closed. Not as armoured as they had been led to believe, John was shot in the throat, thankfully not fatally, and saw VE Day out from a hospital in Scotland.

This is Chris Davison’s (of VersaDock) grandmother, a volunteer in the Women’s Land Army, a vital domestic push by British women to support the war effort. Next to her is Chris’ grandfather, a Leading Aircraftman in the Royal Air Force.

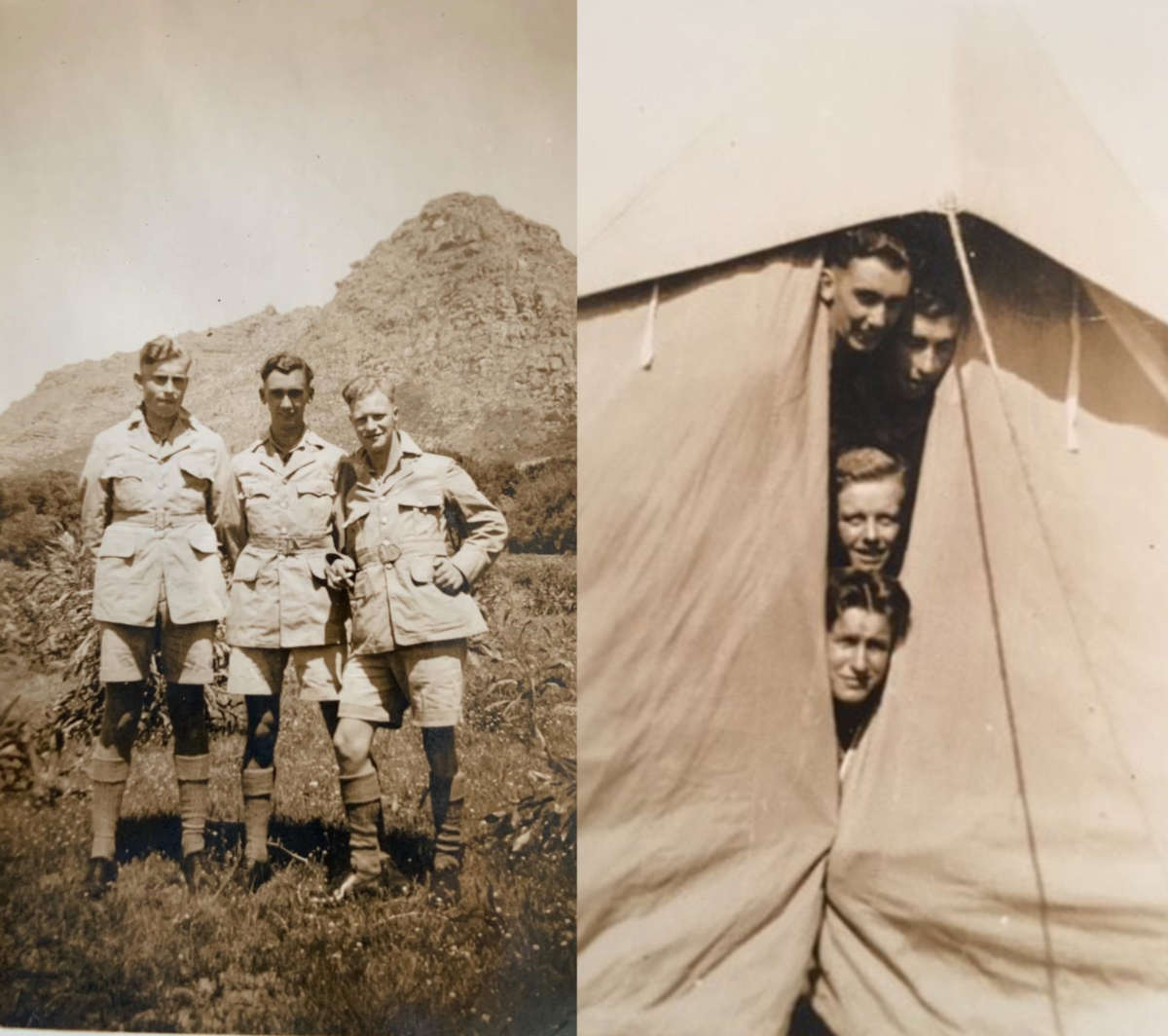

This is Reg Gilham, father-in-law of our Refit Manager Paul Davis. Pictured serving for the RAF in India, Reg is centre in the first image, and at the top of the human pyramid in the second! He was called up in 1941 and left Southampton in 1942, returning to Calshot after the war in 1946. He served as Aircraftsman 2nd class before being promoted to Aircraftsman 1st class and finally to Leading Aircraftsman.

The Directors’ Great grandfather, Harry May, was living at Shipyard House to the north of the boatyard during the war years, which had its perils since German bombers would use clear nights and the moon’s light to bomb Southampton Docks. These would then circle over Lymington on their way home, dropping any spare bombs on the boatyard using the reflected still water as a target. One bomb dropped into the mud opposite Shipyard House (long before the area was dredged) with shrapnel piercing a river-facing stained glass window depicting the original HMS Ark Royal.

Bomb shelters were built during the war to be used when the air raid sirens sounded. On occasion, this could last for up to two hours, which somewhat stalled productivity on the boatbuilding. One shelter was built adjacent to Shipyard House for the MD and office staff & storemen working nearby that now forms the front door and hallway entrance. The roof appears to have been up to 3’ thick!

Another bomb hit further to the south, damaging Seaforth House where the Maritime Coastguard Agency now have their local Lymington office for collaborating search and rescue operations. From this house, they coordinate with the Seaking helicopters and RNLI lifeboats in Western Solent and Christchurch Bay call-outs – or ‘shouts’ as they call them. You can read all about ‘shouts’ here where we chat to one of our on-site RNLI volunteers.